2c. 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis

Royal Gifts from Thailand

Smithsonian – Gallery 2

By the time of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Thailand had established its own National Museum. The Siam Exhibit was much larger than the earlier Centennial Exposition Exhibit, and the Thais even built their own pavilion modeled after Wat Benchamabopit, the Marble Temple, which had just been completed in Bangkok.

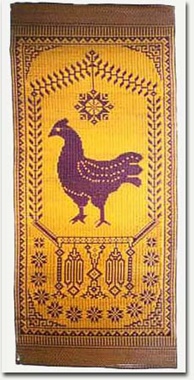

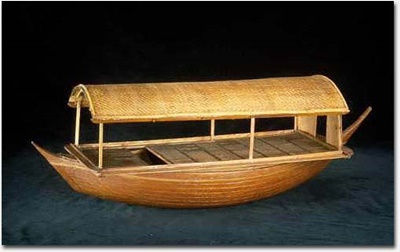

The important insignia items and the Buddhist objects, theatrical gear and other “high arts” were displayed here in the temple. A fishing exhibit, an exhibit of forest products, wood samples, and agricultural tools and products were displayed in other halls.

The majority of the objects in the Siam Pavilion were returned to the National Museum in Bangkok. By 1889 the Thai National Museum was well developed and placed under the supervision of the Department of Education. Before that time there were two successive museums located within the palace walls, the first established by King Rama IV, and the second established by King Rama V in 1874, and moved outside the palace in 1887 to its present location at the former Wang Na, the palace of the Second King.

Although the majority of these objects were sent back to Thailand, ethnological items including hundreds of baskets, fish traps and other fishing gear, models of agricultural implements, and wrought tools from rural areas were given to the Smithsonian Institution at the conclusion of the exposition. Otis Mason, then Head Curator of the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology, also arranged to purchase twelve Thai baskets. At that time, Mason (an authority on American Indian basketry) was planning a major cross-cultural study of the world’s basketry techniques, which he had not completed by the time he died in 1908.

By 1910, the popularity of World Expositions had begun to wane, perhaps because museum exhibits became firmly established as distinct from the trade show business exhibit. Also, like Thailand, many nations were establishing their own national museums and were reluctant to part with important cultural resources that they could house and study themselves.

There were no further exposition exhibit items from Thailand deposited at the Smithsonian after 1904. However, even before the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition King Chulalongkorn had learned that Smithsonian staff and other American scholars were keenly interested in using Thai objects in comparative anthropological research, as reflected in publication as well as exhibition. Consequently, he began to send gifts directly to the Smithsonian.

Recent Comments