1b. Harris Treaty of 1856

Royal Gifts from Thailand

Smithsonian – Gallery 1

After the 1833 Roberts treaty, the next opportunity for gift exchange with the American president came in 1856 when the United States negotiated a new treaty with King Mongkut, Rama IV.

A rather free-thinking scholar and scientist, King Mongkut had been a monk for twenty-seven years during the reign of his predecessor, King Rama III. King Mongkut’s familiarity with Western ideas invigorated the Thai relationship with the West, and a flurry of new treaties was signed during the early years of his reign. The new Thai-American treaty, known as the Harris Treaty, was named for U.S. Envoy Townsend Harris, the colorful, bombastic diplomat who was in a hurry to get to his new post as the first American Consul General and Minister to Japan.

The United States was in a good position to become an important ally to the Thais, as America had no designs on the sovereignty of any Southeast Asian nation, at least at that time. Although actual treaty negotiations were delayed by a month while the Thais and envoy Harry Parkes finished ratifying Sir John Bowring’s 1855 British treaty, once that treaty was finished it became the basis for the American treaty, and Harris had only to negotiate minor points.

Harris’s speeches to King Mongkut and Phra Pin Klao sum up the American position:

“Siam produces many things which cannot be grown in the United States, and the Americans will gladly exchange their products, their gold and their silver for the surplus produce of Siam. A commerce so conducted will be beneficial to both nations, and will increase the friendship happily existing between them.”

Harris went on to elaborate on this position in his formal audience with the Second King, Phra Pin Klao, the next day:

“The United States does not hold any possessions in the East, nor does it desire any. The form of government forbids the holding of colonies. The United States therefore cannot be an object of jealousy to any Eastern Power. Peaceful commercial relations, which give as well as receive benefits, is what the President wishes to establish with Siam, and such is the object of my mission.”

Later, on May 1st, the gifts to King Mongkut from President Franklin Pierce were brought up in a procession to the landing at the Grand Palace. Ship’s surgeon Dr. Wood gives a thorough account of the procedure:

“…about twelve o’clock we started from our quarters in the large state barges that the king had sent for us. First went the boats containing the band; then followed the boat with the President’s letter, which was deposited upon an elevated and canopied throne…the letter itself was laid out in a portfolio of embossed purple velvet; heavy white silk cords attached the seal, which was shut in a silver box ornamented with the relief of the arms of the United States. The cords passing through the seal and box were terminated by two heavy white silk-cord tassles; the whole was enclosed in a box in the form of a book bound in purple and gold; over this was thrown a cover of yellow satin. The marine guard, in two boats under the command of Lieutenant Tyler, escorted that containing the letter. Next came a richly-canopied and curtained boat containing specimens of the presents from the United States to the king. This was followed by the barge containing the commissioner [Townsend Harris], his interpreter, Rev. Mr. Mattoon, and his secretary, Mr. Heuskin, with one of the ship’s coxswains carrying the United States flag. The Commodore, his secretary and I occupied the next boat; and then followed the remaining officers of the suite…the whole procession must have extended along the river for at least half a mile.”

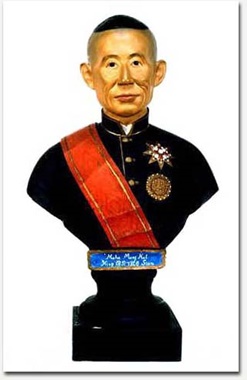

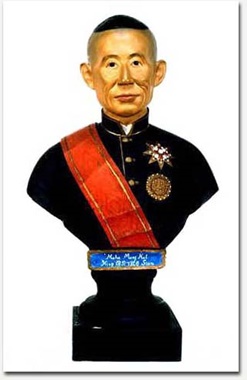

Bust of H.M. King Mongkut, Rama IV

- Gift of King Chulalongkorn, 1876

- Centennial Exposition, Siam Exhibit

- Copper plating, plaster, paint

- Department of Anthropology, cat. no: E27439 (4003-A)

- Height 80.14 cm x width at shoulders 50.6 cm x depth of base 20.6 cm

This painted plaster bust of King Mongkut is a portrait unusually Western in style. King Mongkut’s decorations are the Ancient and Auspicious Order of the Nine Gems and the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant. The years of King Mongkut’s reign are painted in English on a label at the base of the bust.

The artist was most probably Phra Ong Chao (Prince) Pradit Warakan, a distinguished sculptor and director of Royal artists in the Royal Arts Guild Chang Sip Mu. Prince Pradit created sculptures of all of the past kings of Siam for the Royal Pantheon at the Grand Palace at the order of King Mongkut, Rama IV, a commission he completed during the reign of King Rama V.

The norm in the history of Thai art was for artists to remain anonymous and works of art as a rule were not signed. Often these works were collaborative efforts undertaken in service to the King or to other patrons. It is through lists of the Chang Sip Mu that the identities of artists can be discovered. Artists’ careers can be tracked through these lists, however, in the Thai system of ranks, their personal names were dropped in favor of titles of ranks. Unless specific works are cited in written histories of the court as works of a particular artist, we can only speculate that the artist in charge of the particular medium ultimately designed and directed the work.

ความเห็นล่าสุด